Florence Kayemba Ibokabasi:

Human rights agenda appears to have gained traction globally particularly in the South where developing countries are grappling with development and security challenges, leaving governments operating on shoe string budgets which require external assistance based on conditions such as rights based approaches to development programming and policy formulation. This is evident in how the Millineum Development Goals (MDGs), now the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) whose foundation is based on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, have been largely endorsed globally, with various countries setting up Secretariats and incorporating these goals in their requests for for multilateral or bilateral assistance.

It is important to note that embracing of the human rights agenda might be driven by political interests by the donor and state recipient even when that aid is tied to conditions which may be in violation of the country’s traditions and religious beliefs for example the inclusion of women in security forces in Afghanistan, the suspension of anti-gay laws in Malawi, an ultra conservative and religious country whose anti gay legislation sought to criminalise homosexuality.

It might be worthy to note, that there is an increased awareness of human rights globally even in countries where civil liberties were curtailed for decades such as Libya. This is probably responsible for the uprisings in Egypt, Tunisia, Libya and Burkina Faso where regimes were overthrown due to gross human rights violations that infringed on the right to free speech, the right to life and generally socio-economic rights that affect the well being of the populace. It is evident that the increased awareness of human rights by the new generation of youth has made it harder for governments to carry out human rights violations without resistance from the populace eventually.

The emergence of technology such as social media and i mobile communications has helped amplify and mobilise the voices of those affected by human rights violations perpetuated by the state.This is quite different from what it used to be more than a decade ago when there were far less platforms to use to hold governments accountable. Traditional media was censored and mobilising citizens for mass action was quite an uphill task particularly in African countries where police and army were being used to silence the voices of those who were oppressed.

Countries, particularly in the South need to uphold the inalienable rights of their citizens as part of a state culture and not necessarily to please the donors. Regional bodies such as the African Union need to hold members to account for human rights violations and support in particular post conflict nations to build institutions and a national culture that respects the rights of citizens. Using external assistance to build such a culture is not sustainable; if our governments could understand that respecting the rights of the citizens helps improve security and enhances development, perhaps they would work harder at ensuring that civil liberties are respected and the socio-economic rights are upheld irrespective of gender, age and race.

Iain Blackwood:

Iain Blackwood:

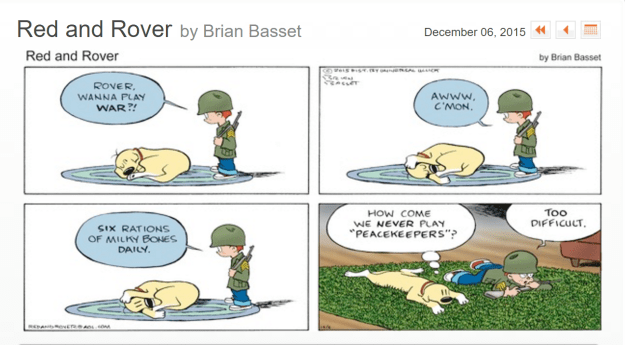

In response to ‘what you envisage is developing in respect of the place of human rights in the international arena and, which may be quite different, what you would like to see emerging’. I do not see that there will ever be an International global system, nation states do intervene in and assist failed states in other nations conflicts in times of crisis, if the outcome is beneficial to themselves and their self-interests. The world will never be a utopia with an International system that controls a Global society (is that not what the UN was set up to achieve some 60+ years ago to preserve world peace). There will always be wars (which have changed in the way they are now fought, won and lost) and some sort of conflict somewhere in the world, be it for religious reasons, National uprisings, disputes for natural resources in times of hardship and because one country or party has what the other wants, to put it in simplistic terms.

I do agree that nations should remain crucial players and that there is also a North-South divide together with a cultural divide and the North can and does assist the South, but the South also needs to assist itself e.g. corruption, Human Rights and its violations, providing for and protecting its own citizens. Furthermore, how can the West impose its beliefs on nations that do not want them, but those nations want aid and assistance on their own terms, but lack the know how or resources to do so. Cultural understanding by the West needs to be better understood when assisting nations.

As has been already mentioned the UDHR is a Global declaration signed by states to protect individuals rights, but is violated on a daily basis by nations to suit their needs and not the needs of their citizens. If the UDHR is to succeed should not more emphasis be made towards reaching those original aims, but be realigned and to meet todays modern-day needs and meet current world developments?

Also the use modern communications highlight the needs and requirements of victims and gets worldwide views and condemnation for the images that are viewed but (one only needs to search the web for such images and HU violations that occur of a daily basis), again countries will only intervene if it suits their needs and wants or has an adverse effect on themselves. Syria is a typical example of who is and who isn’t supporting the fight against ISIL/Daesh. Which is now a worldwide threat.

To conclude Human rights are a necessity and include all articles as laid out in the UDHR to cover the whole of society, but individuals and states need to be held accountable for abuses (Truth Commissions and Transitional justice, ICC under the Rome statute) and enhance their own development of the UDHR. Which ultimately would improve security and development and potentially lead to enhanced peace and security.

Some of you may be considering studying for a

Some of you may be considering studying for a  However, I was more shocked at the tension and aggression which seemed to seep into the corners of everyday life in Atlanta. Here massive billboards portrayed the good life (buy a coke and your life will be meaningful) while people slept on the streets below; there was an onslaught of noise and people who demanded you say how wonderful your day was (OK so I’m a grumpy Brit!); Trump and his vitriol was blaring out from TVs which were everywhere (OK the hotel I was staying in happened to be in the same building as CNN!); people told me how fed up they were with politics and foreigners and women not sticking by their unfaithful men; signs told me I’d have to leave my gun at home if I wanted to get on a plane (which to me is strange in a country not at war, at least on its own soil); and the overwhelming majority of the thousands of participants at the Convention I was attending were white, which smacked of neo-colonialism given the theme was peace, while the majority of people working in the hotels and sleeping on the streets were black. Perhaps I simply didn’t get enough sleep, but I kept seeing messages about about pride and equity, which took on a disturbingly ironic tone in this context (for contrast the third image is from the National Centre for Civil and Human Rights which was outstanding, moving and highly informative – located in the centre of the business district next to the Coca Cola Museum, which appeared to be significantly more popular among tourists – no comment!).

However, I was more shocked at the tension and aggression which seemed to seep into the corners of everyday life in Atlanta. Here massive billboards portrayed the good life (buy a coke and your life will be meaningful) while people slept on the streets below; there was an onslaught of noise and people who demanded you say how wonderful your day was (OK so I’m a grumpy Brit!); Trump and his vitriol was blaring out from TVs which were everywhere (OK the hotel I was staying in happened to be in the same building as CNN!); people told me how fed up they were with politics and foreigners and women not sticking by their unfaithful men; signs told me I’d have to leave my gun at home if I wanted to get on a plane (which to me is strange in a country not at war, at least on its own soil); and the overwhelming majority of the thousands of participants at the Convention I was attending were white, which smacked of neo-colonialism given the theme was peace, while the majority of people working in the hotels and sleeping on the streets were black. Perhaps I simply didn’t get enough sleep, but I kept seeing messages about about pride and equity, which took on a disturbingly ironic tone in this context (for contrast the third image is from the National Centre for Civil and Human Rights which was outstanding, moving and highly informative – located in the centre of the business district next to the Coca Cola Museum, which appeared to be significantly more popular among tourists – no comment!).

Abstract: Before the People’s War (1996) in Nepal, widows were not allowed to wear anything other than the white sari, especially in Hindu families. It was a common practice even among highly educated women. Widows were considered impure and carriers of bad luck as a result of which they were excluded from public events, such as weddings and religious ceremonies. This belief system was deeply entrenched in the history of the country spanning thousands of years. However, when hundreds of women became widows during the People’s War in Nepal, they started organizing themselves and resisting the discriminatory practice of the white sari. This article explores how widows of Nepal subverted thousands of years of this oppressive practice. It also examines the challenges that they faced in the era of the white sari and the citizenship benefits that they have achieved after liberating themselves from the shroud of widowhood.

Abstract: Before the People’s War (1996) in Nepal, widows were not allowed to wear anything other than the white sari, especially in Hindu families. It was a common practice even among highly educated women. Widows were considered impure and carriers of bad luck as a result of which they were excluded from public events, such as weddings and religious ceremonies. This belief system was deeply entrenched in the history of the country spanning thousands of years. However, when hundreds of women became widows during the People’s War in Nepal, they started organizing themselves and resisting the discriminatory practice of the white sari. This article explores how widows of Nepal subverted thousands of years of this oppressive practice. It also examines the challenges that they faced in the era of the white sari and the citizenship benefits that they have achieved after liberating themselves from the shroud of widowhood.

It would be also great to be kept informed of your news after you graduate from the SCID course, and wonderful for SCID students, alumni, Panel members and staff to remain in contact – not least to continue discussing ideas, issues and developments related to conflict and peacebuilding, share resources and opportunities, and continue to consolidate the community of interests that is built around the SCID programme.

It would be also great to be kept informed of your news after you graduate from the SCID course, and wonderful for SCID students, alumni, Panel members and staff to remain in contact – not least to continue discussing ideas, issues and developments related to conflict and peacebuilding, share resources and opportunities, and continue to consolidate the community of interests that is built around the SCID programme. Punam is a new member of the SCID Panel of Experts and is currently a Visiting Scholar at the new Centre for Women, Peace and Security at the London School of Economics (LSE). Punam has conducted research widely in the field of gender, peace and security, and her book Social Transformation in Post Conflict Nepal: A Gender Perspective is being published by Routledge in May (2016).

Punam is a new member of the SCID Panel of Experts and is currently a Visiting Scholar at the new Centre for Women, Peace and Security at the London School of Economics (LSE). Punam has conducted research widely in the field of gender, peace and security, and her book Social Transformation in Post Conflict Nepal: A Gender Perspective is being published by Routledge in May (2016). Hi everyone

Hi everyone